When the exhibit “Art in the Streets” opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles last month, it rekindled the age old debate of graffiti-as-art versus graffiti-as-vandalism. Billed as the “first major U.S. museum survey of graffiti and street art,” by MOCA’s newly appointed director Jeffery Deitch, the exhibit traces the development of graffiti and street art from the 1970’s through today. The exhibit itself has been subject to various controversies, from criticism by the LAPD that the show sanctions the illegal destruction of property; to backlash from within the art community for commodifying the subculture.

When the exhibit “Art in the Streets” opened at the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles last month, it rekindled the age old debate of graffiti-as-art versus graffiti-as-vandalism. Billed as the “first major U.S. museum survey of graffiti and street art,” by MOCA’s newly appointed director Jeffery Deitch, the exhibit traces the development of graffiti and street art from the 1970’s through today. The exhibit itself has been subject to various controversies, from criticism by the LAPD that the show sanctions the illegal destruction of property; to backlash from within the art community for commodifying the subculture.

Since the MOCA show is receiving so much attention, I decided that I would gather a handful of articles that cover the history of graffiti and street art and discuss graffiti in the digital age.

‘The History of American Graffiti’: From Subway Car to Gallery’

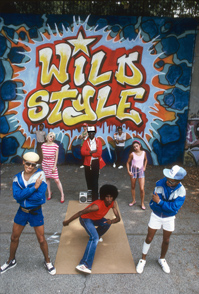

In this installment of PBS Newshour, Roger Gastman and Caleb Neelon discuss their book, “The History of American Graffiti.” They provide a historical context to the emergence of street art and reflect on the relocation of the art form, from the street into the gallery. This is a quick and easy introduction to how street art evolved into one of the hippest global movements of our time.

“‘Taki 183’ Spawns Pen Pals” There was no byline for this July 21, 1971 article that is commonly cited as the first profile written about a graffiti artist. In 1971, Taki 183 was a seventeen year old from Washington Heights who gained notoriety for scrawling his name and street number in bold marker just about everywhere he went. The article calls out a handful of imitators, who only increased in number after this article’s publication. New York Times online subscribers can download the original article in pdf form here.

“Graffiti in its Own Words” by Dimitri Ehrlich and Gregor Ehrlich for New York Magazine. This article is fantastic because of its many primary sources. Page one gives a brief historical introduction. The following pages are a partial transcript of graffiti ‘writers,’ and writers, filmmakers and historians in conversation about the graffiti art movement. The conversation is formatted as a timeline, beginning in 1969 through 2006.

“Subway-style Graffiti’s Shift to Canvas”

Ken Johnson’s New York Times review of the Brooklyn Museum’s show “Graffiti” also gives a concise overview of graffiti’s shift from “low” art to “high”art.

“High-Tech Graffiti: Spray Paint Is So 20th Century” by Geeta Dayal, for the New York Times. Like every other branch of art and culture, graffiti too has been changed by technology. At the most basic level, the Internet has provided a forum for graffiti artists to showcase their work and exchange techniques. However, this article profiles Evan Roth and James Powderly creators of the Graffiti Research Lab, who began using digital technology not just to document street art, but to create it. The duo creates images by launching “throwies” –magnetized battery powered L.E.D. lights– onto city walls, and by writing software used to project digital murals.

“Street Art Way Below the Street” by Jasper Rees for the New York Times.

When a subculture becomes part of the mainstream, or worse, is picked up by consumer culture, those who remain true to the form’s underground roots try reclaim them by further pushing the genre’s original boundaries. In 2010, a group of graffiti artists attempted to reclaim the lost days of risk and adventure through the Underbelly Project– a secret “exhibition” of graffiti art in an undisclosed location, somewhere within the tunnels of the MTA.

Bonus: “Broken Windows” by George L. Kelling and James Q. Wilson

This 1982 Atlantic article by criminologists Wilson and Kelling introduces the Broken Window Theory. The theory recommends maintaining well groomed streets, parks and buildings (i.e. fixing broken windows, painting over graffiti) and cracking down on petty street crime (such as panhandling and public drinking) to lower crime rates. It is often cited in arguments against graffiti and is useful background knowledge for those engaged in the debate about the virtues or detriments of street art.