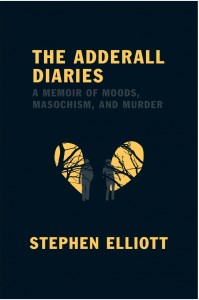

In 2009, Stephen Elliott traveled the country on a D.I.Y. book tour to promote his memoir The Adderall Diaries. (This meant the tour was not sponsored by his publisher; he went where he was invited by readers, often in small towns instead of major cities, and slept on the couches of strangers). His last stop was in New York, where I attended his reading and a lecture on memoir writing.

Elliott told me, “the one rule of memoir is that you don’t lie.” He said you could conceal a character’s identity, and a good way to do this is by changing their physical appearance. “Just never make anyone fat,” he said. “You can make them so sickly skinny they might drop dead at any moment, but don’t make them fat.”

We discussed not lying as it applies to dialogue in memoirs, and how — unless you carry a recorder around with you for your whole life or have a photographic memory — there is no way to use verbatim dialogue in a remembered narrative. Our memories are inherently flawed. They need to be. We forget things because we need to make room for new memories. We forget traumatic things because of our brain’s protection instinct.

“The best thing to do,” Elliott said, “is to try to reflect the intention of what was said, to the best of your ability.”

We agreed that re-creating dialogue in a memoir was hardly a James-Fry-level moral misstep.

I met Elliott three years after the hoopla over James Frey’s false memoir, A Million Little Pieces, which made the subject of truth in memoir a water-cooler topic. (In case you managed to miss it, Oprah had Frey return to her show so she could publicly humiliate him for publishing the lies that she originally praised in her book club.)

Oprah apologized just last week for Frey’s public “lashing” but that’s hardly where this story ends.

Earlier this month, Greg Mortenson was sued for potentially fabricated details about his work building schools in Pakistan and Afghanistan in his bestselling memoir Three Cups of Tea.

Both the Frey and Mortenson controversies have served as stimuli for a larger debate, already stirring, about the value of memoirs and the thin line between memory and truth.

Memoirs have greatly increased in popularity over the course of the past ten years. As their popularity increases, so does the criticism that the genre is worthless, self-absorbed and filled with exaggerative lies — as well as essays in response to the criticism, defending the form and the hard task of cutting into one’s past, synthesizing memory and truth and trauma and making it all fit a narrative arc.

— One of the most recent inflammatory articles was The Problem with Memoirs by Neil Genzlinger in the New York Times Sunday Book Review, which called for “a moment of silence” for the “lost art of shutting up.”

Genzlinger laments the “bloated” genre, which used to be dominated only by writers who had achieved something (that Genzlinger deems) extraordinary. Today, he says, “memoirs have been disgorged by virtually everyone who has ever had cancer, been anorexic, battled depression, lost weight. By anyone who has ever taught an underprivileged child, adopted an underprivileged child or been an underprivileged child. By anyone who was raised in the ’60s, ’70s or ’80s, not to mention the ’50s, ’40s or ’30s. Owned a dog. Run a marathon. Found religion. Held a job.”

Then Genzlinger, who has never written a memoir, goes on to list four prerequisites for writing about your life, while reviewing four recent memoirs in the process. (And hating on all but one of them, obviously.)

— In Get Me Up Close To the Lives of Others at HTML Giant, Roxane Gay says there is an inherent problem with blanket dismissals like Genzlinger’s — a problem with “Problem With” articles. “The ‘problem’ with dismissing memoir, and particular memoirs written by young writers or chronicling the ordinary life is that it assumes we can only become worthy reporters of our lives, and chroniclers of our memories through aging or experiencing something profound,” Gay said. “There is undoubtedly a certain wisdom that comes with age or experiencing something profound but there is also wisdom to be found in ordinary experiences. Neither writing nor remembrance are easy tasks and as such I have a real respect for writers who take the journey inward regardless of what inspired that journey.”

But there is a difference between the slippery slope of “remembrance” and lying. In Notes on Frey, an essay published in Creative Nonfiction, the memoirist Daniel Nester laments the Frey Effect on future writers (“The next Hunter S. Thompson, if there ever is one, should expect knocks on the door by the Authenticity Police, asking him if he really took that many tabs of acid that weekend in Vegas.”) and says there is no way to defend what Frey did. Like Elliot, Nester believes not lying is a rule. But he also believes that, by necessity, all memoirs contain half-truths. He uses The Story of My Life by Hellen Keller as an example. Keller describes, in great detail, becoming deaf and blind when she was 19 months old, an age of which, all neurologists and psychologists agree, humans retain few if any memories.

At the end of Nester’s essay, he has covered a lot of ground — including describing meeting James Frey and interviewing him for a magazine — but still cannot defend him in full.

“I don’t think I can defend what Frey lied about as such as much as his right to imitate and harmonize, these ‘rude improvisations,’ Nester says. “Single-source news stories will still run on the front page and be accepted as fact. Future writers’ parents will wear wires. Everything will be transcribed into a public record; nothing will be edited or crafted, and no one will be dramatized into a character; no one will be disheartened or betrayed as the drudgery of documentation continues. It might be a step forward. But writers will always have the desire to imitate and transform, not simply record, real life.”

— In an interview in The Rumpus, Nick Flynn gets to the heart of the difficulties of writing about your own life, and determining whether your personal truth holds up to actual fact. “Memoir is actually the most egoless genre, even though it might seem ostensibly so much ego-driven,” he said. “In order for it to succeed, you have to dissolve the self into these larger universal truths, and explore these deeper mysteries. If it’s purely autobiographical and ego-driven, it’s going to fail.”

In his 2004 memoir, Another Bullshit Night in Suck City, Flynn explores his relationship with his alcoholic, bank-robbing, homeless father. A great defense of memoir exists not only in Flynn’s Rumpus interview, but in the way he presents his father in the book: sensitively, even lovingly. He shows his father’s negligence as a parent and his inability to care about anyone other than himself. But he also — as most good memoirists do — turns the same harsh lens on himself.

In the Rumpus interview, which is part of series of interviews with writers conducted by Sari Botton, Flynn says, “I was presenting myself in [Another Bullshit Night in Suck City], and especially in the next book [The Ticking is the Bomb], in not the most flattering way either. I think you have to be at least as hard on yourself as you are on whoever the bad guy is. That’s one of the rules. There’s a reason why whatever that bad guy is doing can affect you so deeply.”

— In “A brief history of memoir-bashing,” Slate writer Ben Yagoda show that criticism against memoir is about as old as the genre iteself. “George Bernard Shaw was the first (to my knowledge) to play the veracity card,” Yagoda writes. “‘All autobiographies are lies,’ [Shaw] wrote. ‘I do not mean unconscious, unintentional lies; I mean deliberate lies. No man is bad enough to tell the truth himself during his lifetime, involving, as it must, the truth about his family and friends and colleagues. And no man is good enough to tell the truth in a document which he suppresses until there is nobody left alive to contradict him.'”

Maybe Shaw is right: Frey and Mortenson should have just held on for another few decades before hitting “publish.” Or maybe a more journalistic approach to memoir (watch the video in the side panel) will soon become the norm. Before time figures out the memoir mess, writers should be cautious before selling their work as truth. As my fourth grade teacher, or my grandmother, or — I don’t remember, someone important to me, idon’twanttolie — used to say, “the easiest answer is the truth.”

And if it isn’t, go write a novel.